|

|

| DUNCAN PLAZA |

Introduction Main Library Site | Eye, Ear, Nose & Throat Hospital Pythian Temple | Duncan Plaza Charity Hospital | Rampart Street |

| Click on the images to view a larger version. Use your BACK button to return to this page. |

|

| The Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital and the Pythian Temple were both half a century old when the Main Library opened for business in 1958. Our third featured neighbor, though, Duncan Plaza, is part of the same Civic Center development as the Library building. Designed as the open space element for the Civic Center, the Plaza has been the location for various ceremonial, musical, and other community events over the years. The post-Katrina flood, though, severely damaged the buildings immediately adjacent to the Plaza (the Louisiana State Office Building and the Louisiana Supreme Court), and they have since been demolished. Duncan Plaza remains as open space, but its future -- along with that of the newly-created open space that adjoins it -- is uncertain. |

|

Square 304, bounded by Basin, Franklin, Perdido, and Gravier, included a mix of business and residential uses in 1880, as evidenced by this page from the tax assessment records. We also know, from the 1880 census, that Bernard and Mary Strauss, both natives of France, lived at 262 Gravier with a boarder and a servant. The census also tells us that Henry Turner, a native of Prussia, was at 99 Franklin with his wife, three sons, two daughters, a boarder, and a servant.

Orleans Parish Board of Assessors, Tax Assessment Rolls, 1880, |

|

The Underwriters Inspection Bureau’s street rate slips for Gravier and Perdido Streets show how the properties that would become Duncan Plaza were being used in 1897. The 1200 and 1300 blocks included a mix of residential, commercial, and industrial uses. Though the rate slips show only property owners, we know from the 1910 census that Louis Armstrong lived at 1303 Perdido with his mother and her companion. That corner, along with all of the area bounded by Perdido, Franklin, Gravier, and Locust Streets, lay within the Uptown counterpart to the better known Storyville district where prostitution was confined and tolerated from 1897-1917.

Underwriters Inspection Bureau of New Orleans, Street Rate Slips, 1897 |

|

This early view of what was to become the Civic Center shows the old building stock still intact. In the center foreground is Union Sons Relief Association Hall, better known as “Funky Butt Hall,” an early venue for the music that became jazz (the one-story building on the corner to the right of the Hall is the house where Louis Armstrong lived; the large structure across from it is Fisk School where he was a student). Over to the left, of course, is the Pythian Temple and, across the street, a corner of the old Parish Prison.

New Orleans, La. Office of the Mayor, Annual Report, 1938 |

|

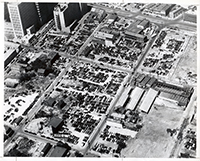

An aerial view of the Civic Center area, this one from the middle of the CBD looking towards the lake, ca. 1947-1949. Note the large black gas holders behind Charity Hospital. They were built in the 1830s when James H. Caldwell started the city’s first gas works, and were finally dismantled to make space for construction of the Veterans Administration Hospital.

Louisiana Photograph Collection, Oversized Photographs, #164 |

|

Another view of the Civic Center site, ca. 1947-1949.

1949 Aerial Photographs #E2 |

|

Another view of the site taken on March 30, 1950, this one from across Tulane Avenue, opposite the Civic Center area. The old criminal court building demolition had only recently been completed and the project to widen Saratoga Street from Tulane to Poydras had just gotten underway.

Municipal Government Photograph Collection, |

|

This aerial view of the Civic Center site, taken on March 30, 1950, shows most, but not all, of the old structures cleared away. Notable among those still standing, at the lower left, is St. Matthew’s Chapel Baptist Church (earlier the hall of Union Sons Relief Association, aka ”Funky Butt Hall”) at 1319 Perdido Street. Note also that the City was able to make a few extra dollars leasing the vacant land on the site for use as parking lots during the time before actual construction started on the project.

Municipal Government Photograph Collection, |

|

A view of some of the buildings awaiting demolition on the future site of the Civic Center, probably on Franklin Street, ca. 1950. Note the Pythian Temple/Industries Building in the background on the left.

Municipal Government Photograph Collection, |

|

This reproduction of a plan from the City Planning & Zoning Commission shows the changes to the street system necessitated by the development of the Civic Center. Note that it shows Loyola (subsequently changed to Saratoga) remaining in use between Gravier Street and Tulane Avenue; that was before the decision was made to place the Library at its present location.

New Orleans, La., City Planning and Zoning Commission, |

|

Mayor deLesseps S. Morrison appointed Brooke H. Duncan as Director of the City Planning and Zoning Commission in 1947. Duncan, a long-time real estate professional, had been working on a plan for a new city government center since the 1930s. He died suddenly in 1950 as the Civic Center was just beginning to take shape. In recognition of his contribution to the project, the Center’s open space was named Duncan Plaza. In this letter from January 17, 1955, his son, Brook Helm Duncan II, thanks the Commission for the honor.

New Orleans, La. City Planning Commission, Subject Files, 1927-1985, Folder 456 |

|

The City made a few extra dollars leasing the vacant land on the Civic Center site for use as parking lots during the time before actual construction started on the project.

Municipal Government Photograph Collection. Department of Property Management, |

|

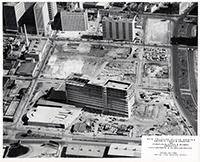

This view of the Civic Center site on March 25, 1956 shows the old court house location completely cleared and the excavation for the Supreme Court building under way. Some parking remains on what was to become Duncan Plaza, but most of that space appears to be in use for construction staging.

|

|

Commissioners Walter Duffourc, Victor Schiro, James E. Fitzmorris and Mayor Morrison welcome Angela Gregory’s bust of John McDonogh to Duncan Plaza, April 1957. The City had the statue moved from McDonogh Place (St. Charles Avenue at Toledano Street) so that the annual McDonogh Day ceremony could move from Lafayette Square and the old City Hall (Gallier Hall) to the new Civic Center.

General Interest Collection -- New Orleans City Government, #177 |

|

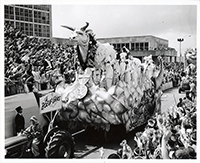

Carnival came to Duncan Plaza in 1959, as the downtown parade route was shifted to pass in front of the new City Hall instead of the newly-renamed Gallier Hall on St. Charles Avenue. The rerouting lasted only four years, though, as the parades returned to the old city hall in 1963. Here the Boeuf Gras float in the 1959 Rex procession makes its way along Perdido Street.

General Interest Collection -- Mardi Gras, #22 |

|

After Mayor Morrison died in a plane crash in Mexico in 1964, a corner of Duncan Plaza was turned into a monument to his life and career. This view shows the 38 foot tall column, incorporating a nine-foot tall statue of Morrison, overlooking a 40 x 100 foot pool/fountain. The latter element was filled in during the mid-1980s and, in 2002, a statue of civil rights leader Reverend Avery Alexander was added, facing the Morrison memorial. The Alexander statue was taken down in connection with the post-Katrina demolition of the adjacent State Office Building and has not yet returned to the Plaza.

Municipal Government Photograph Collection, Department of Property Management, |

|

In 1976, the City dedicated a marble marker in Duncan Plaza in memory of Mr. Duncan. Brooke H. Duncan II (right) was joined by Planning Commission Executive Director Harold Katner, Mayor Moon Landrieu, and an unidentified woman (perhaps his sister, Catherine Duncan Banbury).

Municipal Government Photograph Collection, Department of Property Management, City Hall/Civic Center, #a |

|

In 1980, the City held a competition to select a design team to redevelop Duncan Plaza as a sculpture garden. Mayor Ernest N. Morial’s letter of April 15, 1981 conveyed the good news to landscape architect L. A. Torre that he and sculptor Robert Irwin had won the contest.

Office of the Mayor, Duncan Plaza Project Files, 1979-1981 |

|

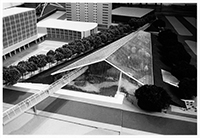

The Torre/Irwin team’s winning design called for an aviary—basically a giant birdcage—to be constructed over most of the Plaza, as depicted in the model shown here.

Office of the Mayor, Duncan Plaza Project Files, 1979-1981 |

|

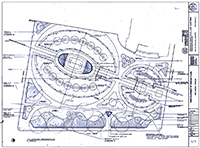

The Torre/Irwin plan for Duncan Plaza proved to be controversial, and the aviary was never really seriously considered. Several years later, Arthur Q. Davis developed a plan that kept the hills or berms envisioned in the earlier plan and also added a small performance pavilion based on the design of the African Hut at Melrose Plantation. The Davis plan, part of which is reproduced here, was built in the mid-1980s.

Building Plans in the City Archives, Renovation of Duncan Plaza, |

|

Charity Hospital | Rampart Street |

|

|

|

|